Let’s Go Oystering

The Skipjack is ready to sail.

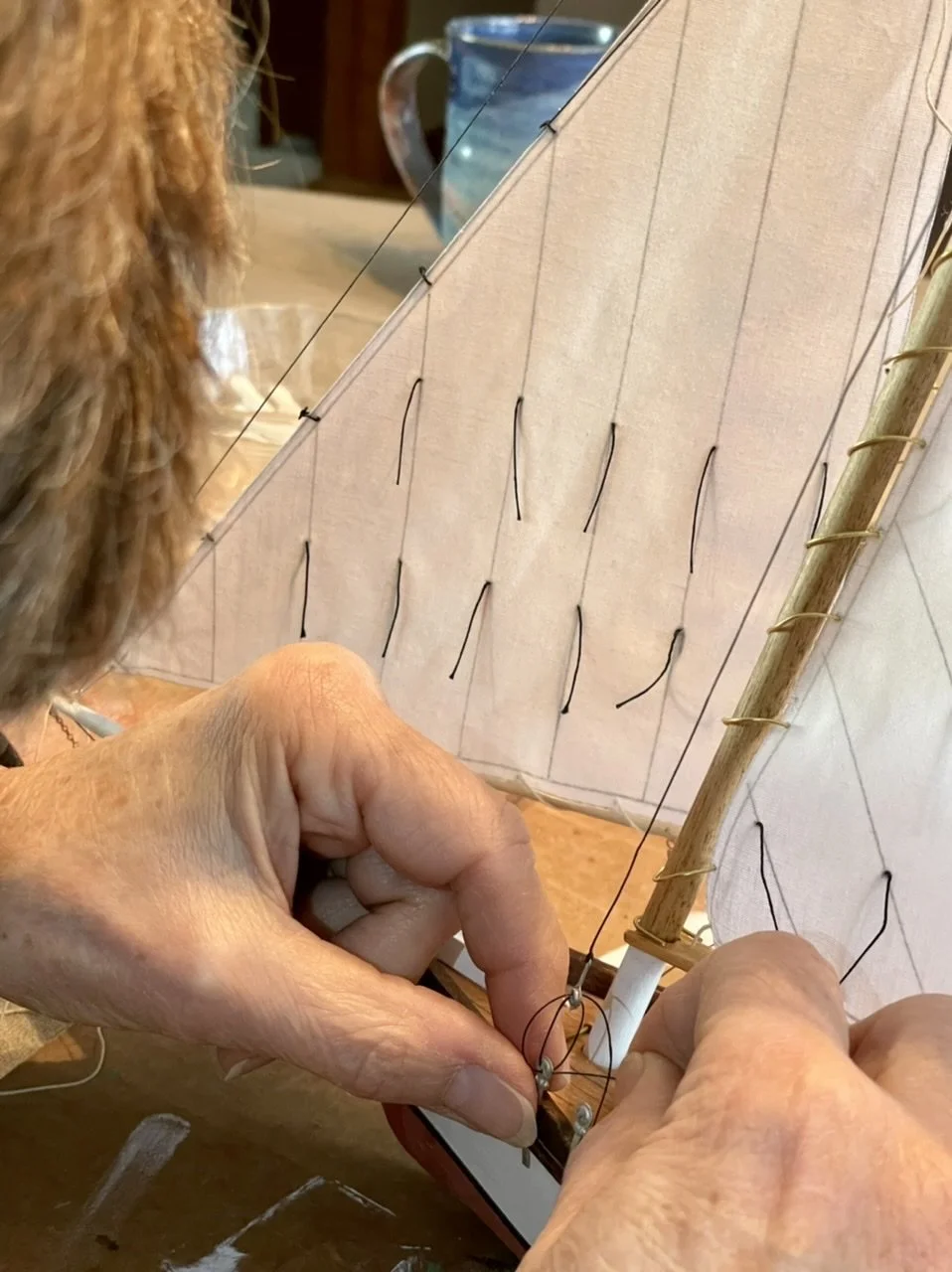

The Chesapeake Skipjack model is complete, at least as complete as it will ever be. Countless hours, plenty of frustration, but lots of fun.

Sometime after Christmas Sue straightened up the basement and came across a box that had been kicking around various basements for more than thirty years. The box, from Midwest Products in Hobart, Indiana, had been opened, but close inspection suggested that, although the supplied glue had long solidified, all the various bits and pieces of a model of a Chesapeake Skipjack were present and intact.

After some internal debate I decided it was now or never; I had the time, the weather was suggesting indoor activities, and Sue had cleared all her sewing stuff off the dining room table. The agreement I made with myself was that I would give it a try and continue until major structural failure, or until things got so bolloxed up that continued work would be pointless. (N.B. the last time I built a model was probably in high school when I slapped together a plastic airplane.)

So, I set up a job board on the dining room table (over the usual cushioned pad, of course). There, the project was visible and enticing. (If I had set up on the workbench in the basement we’d be talking about something else besides skipjacks.) And I went to work—ten minutes here, fifteen minutes there, sometimes even applying a few drops of glue late in the evening after watching an episode of something (such as The Detectorists, which I highly recemmend.)

It was a challenge. Building a model like this requires an “infinite capacity for taking pains,” and a willingness to have your fingers stuck together. Any model builder, in this case me, (and this model required quite a bit of fabrication) really needs to solve a great many intractable problems and to invent a great variety of unique tools (mostly clamps, such as rubber bands). But, that’s the fun of it.

This skipjack model required 365 discreet operations. But, of course, when those operations are done improperly and then have to be undone and redone, that number increases substantially. But then again, fixing messes is part of the fun, is it not?

The one obstacle I had most difficulty with was the overall tininess. Big, clunky fingers have trouble with the minutiae—and can do a lot of damage, especially when they jerk back from some inadvertent disaster. I could never have finished without the help of more nimble fingers and more acute eyesight.

Would I do it again? Maybe, next year. Meanwhile, let’s go oystering,